In the first chapter Patanjali gives us the theoretical aim of yoga, to control the vrittis (thought forms) of the mind. This chapter can be divided into several headings: the different kinds of thought forms, the practices to control them and the different kinds of superconscious experiences, culminating in the highest experience of Samadhi, or enlightenment. But, it is not that easy to get to Samadhi. The second chapter tells the student how to prepare him/herself by laying the proper foundation, then gradually building until that level is reached.

Y.S. 2.1 Tapah svadhyaya ishvara pranidhanani kriya yogah

Tapas – heat, accepting pain as purification

svadhyaya - self study and the study of spiritual books

ishvara - supreme being

pranidhanani - surrendering

kriya - action

yogah - yoga

Kriya yoga, the yoga of action, which is burning zeal in practice, self study and surrender to a higher power.

Tapas is often translated as effort and is often thought of as austerity. But it stands for something different here. Tapas means “to burn or create heat”. Anything that is burned will be purified. For example, the more you fire gold, the more pure it becomes. Each time it goes into the fire, more impurities are removed.

Tapas also refers to self-discipline. Swami Satchidananda describes it this way: Normally the mind is like a wild horse tied to a chariot; the intelligence is the charioteer, the mind is the reins and the horses are the senses. The Self, or the true you, is the passenger. If the horses are allowed to gallop without reins and charioteer, the journey will not be safe for the passenger. Although control of the senses and organs often seems to bring pain in the beginning, it eventually ends in happiness. If tapas is understood in this light, we will look forward to pain; we will even thank people who cause it, since they are giving us the opportunity to steady our minds and burn out impurities.

This brings me to my favorite quote from the movie Evan Almighty. In the movie, “God” says to a woman who is leaving her husband because he is not quite the man she married: “Let me ask you something. If someone prays for patience, do you think God gives them patience? Or does he give them the opportunity to be patient? If he prayed for courage, does God give him courage, or does he give him opportunities to be courageous? If someone prayed for the family to be closer, do you think God zaps them with warm fuzzy feelings, or does he give them opportunities to love each other?

This is tapas in action.

On our yoga mat, tapas means showing up to practice, whether you feel like it or not. It also means doing the poses you don’t like. To help you learn to like those difficult poses, you are allowed to modify them and use props to make those postures more accessible. It means letting go of the drama that surrounds any discomfort and breathing into it. However, it doesn’t mean physical pain. That would go against the first yama of ahimsa or non-violence.

Self-study involves being able to see one’s true, capital “S” self. This doesn’t mean focusing on one’s own feelings and problems. Both the yoga texts and modern psychology tell us that extreme self-centeredness is one sure way to depression. Anything that will elevate your mind and remind you of your own true nature, of your inner divine self should be studied; texts such as the Yoga Sutras, the Bhagavad Gita, the Bible, the Koran. This type of self-study will take you on a journey to your inner self to help you see if you are living a life in alignment with the spiritual path you are on.

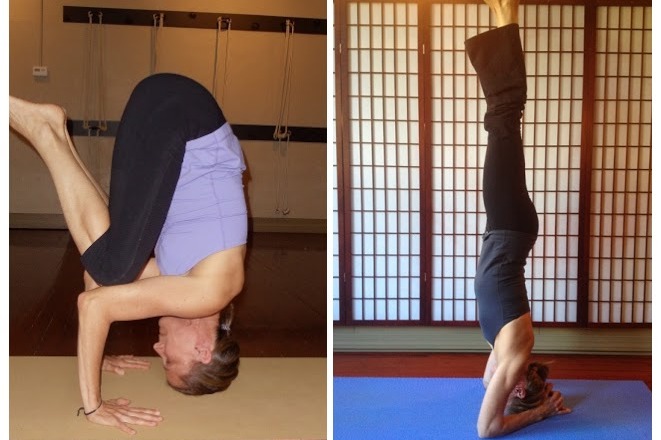

On your yoga mat, this translates into watching your physical alignment. We often think we are doing something, but only when we truly open our eyes to look and see if we really are doing what we think we are doing does the insight come. We may wonder why we are not progressing on the path. Often it is because we are out of alignment in some way. This is tough because our ego gets in the way. We are often willing to sacrifice alignment to reach a goal. Or, maybe we misunderstand what is important. In yoga you might think you are stretching yourself, but really you are stretching toward your Self.

Surrender is often the hardest spiritual practice. This is the practice of letting go of outcomes and of letting go of your own agenda. The way yoga works, the way it truly works is to dedicate your practice to a higher goal, or to dedicate your practice to others. The Bhagavad Gita tells us that we only entitled to our actions, not the fruits of our actions. An analogy is often given of a flower blooming; it doesn’t try to bloom, it just blooms.

Letting go also means letting go of your stuff. We often have much more stuff than we need and letting go of it is hard. The inability to let go is another way of being stuck. In order to let go of stuff means letting go of memories, of the past, of possibilities that once were. Not letting go is another way of staying stuck. There is this saying about not being able to reach into the future if you cannot let go of the past.

On your yoga mat, this means to do your poses in your best possible alignment, with your heart and soul and to not worry if you achieve the final form of the posture. Most of us get hung up on the final form of the posture and don’t value the intermediate steps. I can see this when I ask people to slow down and not go into the final pose right away. If they can do the pose, most people find it hard to restrain themselves. When we stretch ourselves, the goal is not to stretch towards the pose, the goal is to stretch toward the Self.

Surrender is also the ability to relax. We practice this at the end of every class in Savasana. Many times when I adjust people in Savasana I feel their tension. As I lift their arm, I feel them helping me and their arm feels stiff. If they were relaxed and I was to let go, the arm should fall to the floor, but it often remains held rigidly in the air. This is because there is so much tension in our lives. We often feel as if we are on guard protecting ourselves. Savasana is where we can practice letting go.